702-660-7000

702-660-7000

As someone who’s spent years in the financial industry, I’ve seen my fair share of books promising the secret to building generational wealth. “What Would the Rockefellers Do?” by Garrett B. Gunderson and Michael G. Isom is the latest entry in this genre, and while it offers some valuable insights, it also falls into some common traps that could lead readers astray.

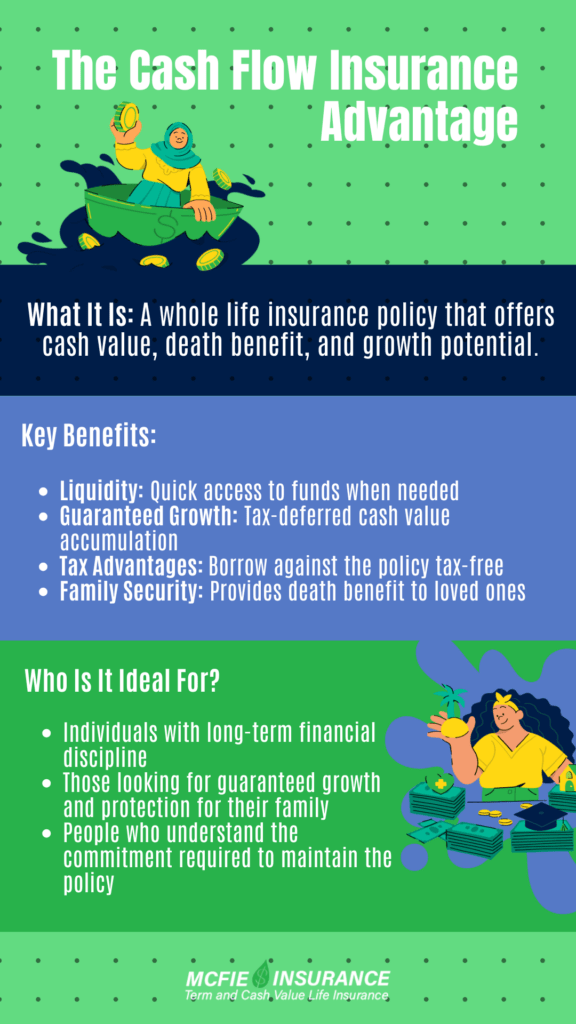

Let’s start with the positives. The authors do an excellent job of challenging conventional financial wisdom, particularly when it comes to the value of whole life insurance. Their explanation of Cash Flow Insurance is thorough and compelling. They correctly point out that “Cash Flow Insurance is instrumental in creating economic independence” (p. 26) and that it can provide “liquidity, savings, the death benefit, and the guarantees” (p. 26) that many other financial products can’t match.

The book’s emphasis on creating value and increasing personal productivity is also commendable. The authors rightly state that “Create value and dollars will follow” (p. 157), which is a principle I’ve seen play out time and time again in my work with clients.

However, where the book starts to lose me is in its zealous advocacy for complex, multi-generational wealth transfer strategies modeled after the Rockefellers. While these strategies might work for the ultra-wealthy, they’re simply not practical or necessary for most people.

Take, for example, the authors’ enthusiasm for creating a detailed “Statement of Purpose” for your trust. Garrett’s personal statement takes up “fifty-one pages out of my eighty-seven-page trust document” (p. 135). That’s a lot of legalese for something that, frankly, most people’s descendants aren’t likely to pore over hundreds of years from now.

The authors seem to have fallen into the trap of thinking that everyone should aspire to create a financial dynasty. They write, “Is it possible for you not just to leave your kids better off than you were, but to spark a financial legacy of wealth and empowerment that lasts for generations?” (p. 2). While this sounds appealing, it’s important to ask: why do you really care what someone is going to do with the money hundreds of years after you die?

We believe that everyone should have a trust, but not every kind of trust. A dynasty trust, like the ones the authors advocate for, is good for some people but not most people. For the vast majority of folks, a simpler trust that takes care of their immediate family and maybe the next generation is more than sufficient.

The book’s fixation on the Rockefeller method of wealth preservation can lead readers down a rabbit hole of unnecessary complexity. For instance, the authors suggest setting up a board of trustees to manage your family wealth after you’re gone, complete with a “trust protector” to oversee the board (p. 79). For most families, this level of complexity is not only unnecessary but could potentially lead to conflicts and complications down the line.

Another area where the book misses the mark is in its somewhat cavalier attitude towards spending. The authors promote the idea of a “Living Wealthy account” (p. 172) for guilt-free spending. While I’m all for enjoying life, this approach could lead some readers to overspend, potentially jeopardizing their long-term financial security.

The book also tends to oversimplify complex financial concepts. For example, the authors state that with Cash Flow Insurance, “you can earn interest rather than paying it, cut out the middleman, and do what the banks do” (p. 184). While there’s some truth to this, it glosses over the complexities and potential pitfalls of using life insurance as a banking system.

That said, the book does provide some valuable insights into the power of whole life insurance when used correctly. The authors rightly point out that “Cash Flow Insurance allows you to have liquidity and tax advantages” (p. 184). This is indeed one of the key benefits of properly structured whole life policies.

The book’s emphasis on becoming your own banker is intriguing, but it’s important to note that this strategy isn’t for everyone. It requires discipline, financial literacy, and a long-term commitment. The authors could have done a better job of highlighting the potential risks and drawbacks of this approach.

One of the strengths of the book is its critique of traditional retirement planning. The authors correctly point out that “401(k)s are on their way out” (p. 60) and that relying solely on market-based investments for retirement can be risky. Their advocacy for more stable, guaranteed financial products is a perspective that’s often overlooked in mainstream financial advice.

However, the book’s dismissal of budgeting as something that “sucks” (p. 153) is problematic. While their concept of “Value Based Spending” has merit, it doesn’t negate the importance of having a clear understanding of your income and expenses. Budgeting, when done right, isn’t about deprivation—it’s about intentionality and awareness.

The authors’ discussion of the four types of expenses—destructive, lifestyle, war chest, and productive—is insightful (p. 166-167). This framework can be a useful tool for readers to evaluate their spending habits and make more intentional financial decisions.

One area where the book shines is in its explanation of the difference between price, cost, and value. The authors write, “The only measure worth considering is if the value you place on a purchase is greater than the cost” (p. 165). This is a nuanced perspective that can help readers make more thoughtful financial decisions.

However, the book’s emphasis on using life insurance as a wealth-building tool sometimes borders on excessive. While whole life insurance can be a valuable part of a financial plan, it shouldn’t be seen as a cure-all. The authors could have provided a more balanced view by discussing other financial tools and strategies in more depth.

The book’s discussion of the “Wealth Capture Account” and “Automatic Wealth Ladder” (p. 180-182) offers some interesting ideas for systematic saving and wealth building. However, the suggested 18% savings rate might be unrealistic for many readers, especially those just starting out or dealing with significant debt.

In conclusion, “What Would the Rockefellers Do?” offers some valuable insights into alternative wealth-building strategies, particularly around the use of whole life insurance and the concept of becoming your own banker. The authors challenge many conventional financial planning norms, which can be refreshing and thought-provoking.

However, readers should approach the book’s more extreme recommendations—like creating complex, multi-generational trusts—with caution. For most people, a simpler approach to financial planning and wealth transfer will be more appropriate and achievable.

The book’s strengths lie in its explanation of Cash Flow Insurance, its emphasis on value creation, and its challenge to traditional retirement planning wisdom. Its weaknesses include an oversimplification of complex financial concepts, an overemphasis on dynasty-style wealth transfer, and a sometimes cavalier attitude towards spending.

Ultimately, while “What Would the Rockefellers Do?” provides food for thought, readers would do well to remember that they don’t need to emulate the Rockefellers to achieve financial success. For most people, a solid financial plan, a simple trust, and a focus on creating value in the here and now will serve them far better than trying to control their wealth for generations to come.

At McFie Insurance, we believe in tailoring financial strategies to individual needs and circumstances. While some of the ideas presented in this book may be useful, they should be considered as part of a broader, personalized financial plan. Remember, you don’t need to build a financial empire to live a rich, fulfilling life and leave a positive legacy for your loved ones.

Tomas P. McFie DC PhD

Tomas P. McFie DC PhD

Tom McFie is the founder of McFie Insurance and co-host of the WealthTalks podcast which helps people keep more of the money they make, so they can have financial peace of mind. He has reviewed 1000s of whole life insurance policies and has practiced the Infinite Banking Concept for nearly 20 years, making him one of the foremost experts on achieving financial peace of mind. His latest book, A Biblical Guide to Personal Finance, can be purchased here.